|

Library Service Then... The front desk of the Rose Memorial Library was the place to request books in this closed-stack environment. This photo from the 1940s or early 1950s also shows two important pieces of history in the back- ground: a war relief poster and a portrait of Lenox Rose, who donated the funds to build the library. |

As increasing numbers of New Jersey colleges and universities have begun participating in Q&A/NJ, the statewide chat reference service, Q&A/NJ has been able to improve services to their academic audiences. Now, when students connect to the service and identify themselves as college students, they will be matched with academic librarians staffing Q & A /NJ, which will provide assistance appropriate to their level. If no college librarians are available, students will be shifted to other librarians, but college students will have better access to academic librarians during the times when they are staffing the service.

The Reference Department is piloting additional reference hours in the early evening this fall, adding coverage from 6:00 to 7:00 p.m. , Sunday through Thursday. The additional hours of service are in response to higher numbers of students taking evening courses, for whom reference help prior to class can be useful.http://depts.drew.edu/lib/visions/Visions16.php#top

The 9/11 Commission Report asks, "How can the United States and its friends help moderate Muslims combat the extremist ideas?" It then includes several pithy statements about the role of libraries.

The Report also expresses concern for the protection of privacy rights in light of the new powers in the investigative agencies of the government and recommends:

Friends of the Library |

|

THE DIRECTOR'S CORNER:Precincts of Privilege |

While working my way through a pile of publishers' catalogs, I was struck by the number of new fall titles that dealt with ethics. There was the Ethics of Teaching, Ethics and the Metaphysics of Medicine, and The Ethics of Mourning: Grief and Responsibility in Elegiac Literature. There was even Sport, Play, and Ethical Reflection. And my favorite, Ethics without Principles.

You can search the Drew library catalog for books that have the word 'ethics' embedded in the title and be rewarded with an astonishing array of topics focused under an ethical lens. I've been thinking about adding yet another title to that inventory, a book from my own pen---a book on the library and ethics. What would you expect to find between the covers of my proposed volume? Borrower responsibility to return books on time? How about the need to respect the right of others to a serene place for studying, free of the siren call of cell phones? The perennial debates about the ideologies of the Dewey Decimal and Library of Congress classification systems? Or how you allocate limited resources for the competing needs of undergraduate and graduate students? How about the dilemma for librarians in the face of the USA Patriot Act? And certainly the evils of book mutilation and theft? While all of these prick sensitive ethical nerves, they don't delve into the theme that interests me most.

Consider the simple act of purchasing something new for the library. It doesn't make any difference whether that item is a book, journal, DVD, an electronic book, a collection, or a database. For the sake of simplicity, let's assume that we are dealing with a book. Choosing that book is a decision laced with ethical complexity, for it is an act of discrimination; an act that gives that book privilege over the others that are not selected. The burden of that choice is not simply that the book is purchased, thereby benefiting one publisher and author over others. It is rather that the library does much more to that volume than merely paying for it and shelving it.

The library enlarges the book's life. It catalogs it and places it in a database with advertising tags for author, title, and relevant subjects that enhance the chances of the book being noticed and actually used. The library is thereby saying to its patrons, "Pay attention to this volume. It is important, a volume chosen over many others. We brought it in from the cold."

We often talk about library privileges---what groups of people qualify for different levels of borrowing privileges. The library stacks are a precinct of privilege, too, for the volumes residing there have been granted permanent residency, while many other titles have been denied even visiting rights, except those negotiated by interlibrary loan.

In order to ensure that such acts of "privileging" are meted out with integrity, principles for purchasing are essential. Consequently, responsible libraries spell out those principles, guided by the American Library Association's Library Bill of Rights.

Embodied in the Drew stacks is the university's commitment to intellectual freedom. Regardless of reigning methodologies, schools of thought, and canonical authors within the disciplines, counter-perspectives will also be found. The holdings of the library will always support the current curricula, yet be much broader. Emphasis is given to primary sources, so that the spokespersons of a perspective or tradition may be read in their own voices, not merely through the censorship of their critics. Consequently, the heretical and the orthodox sit side by side in the stacks. Scholars are there in abundance who would never be asked to lecture on campus. As the former associate director of the Drew library, Jean Schoenthaler, is fond of quipping, "A great research library will have ample books to offend everyone."

A story may make the point. Some years ago, a university president phoned her library director in a panic. She had just learned that several representatives of an ultra-conservative group, one tied to a major donor, were coming to meet with her and some faculty and had signaled that they also intended to interrogate the library catalog for authors and journals they favored. "What are we to do?" she implored. "Nothing," was the emphatic reply, "we're a liberal institution." With irritation the president countered, "That's just the problem; my guests expect to confirm their suspicion that the conservative perspective is not represented here. Can we do something in the next few days?" The president then heard the consoling and chastising words: "We are a liberal institution. Your visitors will find many titles reflecting their views. And many others, too."

As for the title of my book? The Politics of Inclusion has a nice ring to it, but I think that has already been taken. Perhaps Choosing the Right and the Left will do.

— Andrew D. Scrimgeour

References

Atkinson, Ross. "Library Functions, Scholarly Communication, and the Foundation of the Digital Library: Laying Claim to the Control Zone," Library Quarterly 66 (July 1996).

"Collection Development Policies and Procedures," Drew University Library. depts.drew.edu/lib/faculty.html

Kean, Thomas H. The Politics of Inclusion. New York: Free Press, 1988.

"Library Bill of Rights," American Library Association, 1948, 1986. www.ala.org/ala/oif/statementspols/statementsif/librarybillrights.htm

|

Director Andrew Scrimgeour with Friends of the Library Advisory Board at a planning meeting for the January 29 Dinner Gala. Pictured are Deborah Strong, Epsey Farrell, Professor Merrill Skaggs, Dr. Scrimgeour, Professor Jonathan Rose, President of the Friends Lynn Heft, and Bertha Thompson. |

The Library acknowledges generous contributions from:

Bruce Audretsch

Mrs. Sandra L. Bergold

Mr. Finn M. W. and Dr. Barbara Morris Caspersen

Dr. Cynthia Cavanaugh

Professor Emeritus Charles Courtney

Robert E Fowler

David and Carol Friend

Elizabeth A. Greenfield, Esq.

Nancy L. Helmer

Miss Julia LaFalce

Bruce Knigge

Rosemary M. Manifold

Lucy Marks

Philip Oxnam

Mr. and Mrs. John Robinson, Jr.

Mrs. Lois Sechehay

Professor Emerita Joan E. Steiner

Memorial Gifts

In memory of Rev. Garfield G. Steedman, B.D., 1940, from C. Marian Steedman, in behalf of the Bulls and Bears, a group of nine ministerial couples in the North Indiana United Methodist Conference.

In memory of Dalys Oxnam Jaecker

from Bertha T. Thompson.

In memory of Granville Conway

from Bertha T. Thompson.

|

Emmeline Brancato, CLA junior, gets a grip on the semester with a scoop of Italian Ice served outside the Library in September. She is one of fifty-three Drew students employed by the Library this fall. Throughout the year, library student employees will clock over 18,000 hours on the job, the equivalent of ten full-time employees. |

By Suzanne Selinger

Theological Librarian

I thought I was done with Charlotte.

Background

In 1998, my study of the collaboration and relationship of Karl Barth, the dominant theologian of some five decades of the twentieth century, and his secretary and theological assistant, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, was published. In the following years I gave some lectures on the subject and wrote a couple of articles based on material I had not yet used.

In 2000, the correspondence for the years 1930-1935 between Barth and Eduard Thurneysen--the good friend and colleague with whom he worked out his earliest theological manifestos was published in a 985-page volume. The volume also includes correspondence between Thurneysen and von Kirschbaum, who often served as correspondent in Barth's stead, but who is more than his voice in this exchange. The years covered by the volume were those of the tumultuous rise and seizure of state power by Hitler and his followers. To secure control, a uniform, unbending culture of nazification was extended into the institutions and lives of the German people.1 Barth, professor of Reformed theology at the University in Bonn and, as such, a state employee, became one of the principal leaders of the Bekennende Kirche -henceforth, BK--the opposition movement within the German Protestant Lutheran and Reformed churches.

In the same years, a personal crisis, also of uncontainable dimensions and wrenching effect, occurred. Charlotte had come to live in the Barth home in 1929, because Karl maintained he needed her there to get his work done. His wife, Nelly, objected from the start. In March, 1933, she told Karl that she could no longer tolerate the situation: Charlotte must leave the household. In response, Karl proposed that they acknowledge the long-evident truth that their marriage had been a mistake, and, for the sake of all involved, including their five children, it should be ended by divorce. Nelly refused. Letters between Karl and Eduard and between Charlotte and Eduard on the situation, and the recurring references and allusions to this subject throughout the volume, depict the complex connections among personal, theological, professional, and political contexts. They convey the frightening pace and temper of these contexts and bring into sudden daylight and everyday life a reality we hitherto knew only as a sketch based on collected memories. I was asked to review the volume of correspondence and could not decline: the story had too long been distorted by Barth's enemies and avoided by his followers.2

I wrote one more article in 2000, on von Kirschbaum and Barth in which I took a long view--surely the valedictory view--of the research process that went into my book.3 Finally, I was free to enjoy the lovely post-book time of coasting a little, exploring topics for the Next Big Project, and looking around and catching up with the stack of journals, book announcements, and article references that pile up on and around one's desk while one is enmeshed in writing and the publishing process. However, catching up proved damaging to the cause of moving on.

The First Footnote

While researching Charlotte von Kirschbaum and wondering about her vocational options in education and the German church, I had been in fruitful correspondence with a German scholar who directed a project documenting the history of women in the German Protestant church. She sent me a copy of the group's newest publication: Der Streit um die Frauenordinationin der Bekennenden Kirche: Quellentexte zu ihrer Geschichte im Zweiten Weltkrieg, a study of the debates that took place in a special committee within the BK during WW II on the question of the ordination of women in the Protestant German evangelical churches---a subject made more compelling as more and more pastors were conscripted into the Nazi army and thoughtful women were so successfully serving as interim pastors and wondering why ordination was being denied to them.

A confrontation between realities and policies, and between early German feminism and dogmatically anti-feminist Nazism, and between the Rhenish Lutheran pastors, whose social conservativism traveled with them into the opposition movement, was definitely an interesting subject. It was also, I assumed, a new subject for me. Barth, dismissed from the university for refusing to proclaim loyalty to the Fuehrer, returned with his family and von Kirschbaum to his native Switzerland in 1935. Even before their move, in little over a year since Barmen, tensions between Barth and the BK had arisen, and their relations had consequently deteriorated over such issues as compromise with the powers of the day (to which Barth characteristically said, "No!") and whether and how political opposition should be carried out.

I always scan the index to a book before reading it. Barth was of course mentioned in the introductory section of Streit um die Frauenordination as a key founding member of the BK in the 1930s. Unexpectedly, I found an index reference to the main section, "Quellentexte," for Charlotte von Kirschbaum. Hooray--- but what was she doing amidst these documents and this debate?

Footnote 48 expands upon a postscript in Document 82, which is a letter of November 1942, on the BK deliberations written by committee member Hermann Diem to Ernst Wolf, both of them colleagues and trusted friends of Karl and Charlotte. Diem is disgusted with the rigid anti-ordination stance of the dominant voices in the assembly. In the postscript, he tells Wolf he is sending him an informative contribution to the debate by a non-committee member, "Tante [Aunt] L." This is code for Charlotte von Kirschbaum---her nickname was Lollo, and the Barth children called her Tante Lollo after she moved into the Barth household. The footnote provides this identification and the title of her piece: "Einige Anmerkungen zu Abschnitt II des Protokolls. Der Dienst der Frau im NT [Remarks on section II of the Committee's protocol: The roles of women in the New Testament.]." Diem found persuasive von Kirschbaum's "positive" reading of scriptural passages he had previously dismissed as irrelevant outside their historical context. But it was too late for anyone to influence the debate. The committee had decided that, at the end of the war and upon the return , or resupply, of the 'real' rectors, women were to relinquish preaching and administering the sacrament, and confine their activities to those of curate.

So von Kirschbaum had participated in this interesting debate. And so a biographer had stumbled upon another invisible strand in her life, recorded in another unpublished text. I had to find that text! This turned out to be reasonably easy, after satisfyingly causing some confusion in the Barth-Archiv in Basel . I e-mailed the archivist, a fine, highly respected scholar with whom I had become acquainted on a visit to Basel , and asked for a copy of von Kirschbaum's essay for the BK. He e-mailed back that he didn't think it existed. I said it certainly did, and faxed him Footnote 48. Within a few days, he sent me an e-mail with two versions of the text. A research mini-coup! I later got a third copy, from the women's history group that had published Streit um die Frauenordination.4

As I read von Kirschbaum's commentary, I realized it was also an early version of one of the major parts of the work we know as Die Wirkliche Frau, the collection of her essays based on a lecture series she gave.5 The argument of the BK piece paralleled that of the essay, "Der Dienst der Frau in der Wortverkhndigung" ["The Role of Women in the Proclamation of the Word"]. Here, too, was von Kirschbaum's uncommon way of proceeding from the key Scriptural passages that were typically used to enforce gender stereotypes, and demonstrating contextual and especially intratextual exegesis which leads to different conclusions. Many of her core ideas were recognizable in this text, while some were new to me and seem not to have appeared after this presentation. One, on the roles of women and men in the church, was of particular interest in its trenchant and creative revision of tradition. The church roles are different, just as men and women are different and their respective spiritual gifts are different. Men proclaim the Word (the Teaching church); women listen (the Hearing church). However, the roles are not essentialist but representative. While clearly defined roles and their interrelations, as such, are necessary for order, and the church roles generally hold as described, they can and should be interchanged from time to time. There is nothing like this in von Kirschbaum's later published texts, or in Barth. Would that there were.

The Second Footnote

At about the same time, I encountered another arresting footnote, one that supplied a different kind of information. It did not widen the sphere of von Kirschbaum's life; rather, it opened up a text to strata I had not seen and processes I had only hypothesized. In the note, Charlotte explained how Die Wirkliche Frau had come into existence and evolved as it did. In doing so, she provided a map of her collaboration with Barth, which was always the heart of my subject.

The footnote was in an article by Regine Munz on Charlotte von Kirschbaum and Simone de Beauvoir.6 In the note, Munz quoted a letter from Charlotte to a friend in 1946, as evidence of von Kirschbaum's long-standing interest in the subject of gender. Charlotte writes to her friend that she and Barth are focusing on humanity in preparation for book III, volume 2, of the Church Dogmatics. Barth defines humanity as "being with one's fellow human," the original and primary form of which is the being [with each other] of man and woman. In the course of their work, Charlotte relates, she retrieved her own past work on the subject, of which we have just seen a significant part. She showed the work to Barth, and it "found grace in his eyes." Now she sees the possibility of bringing it to a completed form! However, since she last worked on it, CD III/1, with its excellent exegesis of Gen.2:18ff on the creation of woman, which is an important focus of her work, has appeared, and she must consider her exegesis anew. Then she will write a Protestant answer to Gertrud von Le Fort's book, Die Ewige Frau. Perhaps as such a specifically delineated task, written "in more concise and readable form," she can say what she had over the years produced in exegetical work on this topic.

Close readers of CD III are aware that Barth cites von Kirschbaum's WF several times. He also refers to his foundational exegesis of Gen.2 in III/1: I think he is, properly, both crediting and limiting von Kirschbaum's contribution on his subject. Readers of my book may also remember a remark I quoted that von Kirschbaum made to Barth from time to time in their work on male and female humanity: "...you stole that from me."7 Unaware, at the time, of her commentary of 1942, for the BK debate on ordination, or of other exegetical writings prior to WF --at least on Genesis 2, which the Munz footnote strongly implies--I had assumed that von Kirschbaum's remark to Barth about taking her ideas referred only to their ongoing dialogue as Barth produced the Dogmatics. When I tried to describe their collaboration, I called it an exchange and used the image of a thick braid, the strands of which can't be sorted out and measured. I'd still say that, generally, but in at least one central instance, we now have a definite record of exchange and a much closer, longer cross-temporal view than before.

1Rather, the German people as re-defined by Nazism.

2See my review article, First impressions of Karl Barth - Eduard Thurneysen: Correspondence Vol. 3 http://www.unibas.ch/karlbarth/dok_letter3.html#selinger

3See "My Book and My Inner Librarian," in Visions, Vol. 8, 2000 at http://depts.drew.edu/lib/visions/visions8.php

4i.e., be stubbornly persistent if you have reason to think that something exists and is worth hunting for.

5Originally given as a lecture series...

6Regine Munz, "Aus Liebe zur Freiheit Charlotte von Kirschbaum liest Simone de Beauvoir," Zeitschrift fur Dialektische Theologie 16:2 (2000), note 19, pp. 211-12.

7Barth told Eberhard Busch about this remark. See my KB and Ch.vK, pp. 89-90.

|

The Rose Memorial Library main foyer in its first year of service, 1939. The polished floors, black columns, and etched glass globe fixtures brought a fashionable and modern look to the large room, which housed the card catalogues. |

Linda Connors, Head of Acquisitions and Collection Development, contributed two articles to Epilogue: Canadian Bulletin for the History of Books, Libraries, and Archives (vol. 13, 1998-2003), "Creating a Useable Past: The Role of the Quarterly Review in Shaping a National Identity for its Provincial Readers, 1820s-1850s," and "The Periodicals and Newspapers of Nineteenth-Century Britain and its Empire: Three Case Studies in 'Being British'," with Mary Lu MacDonald and Elizabeth Morrison.

Lucy Marks, Methodist Cataloger, was honored by her alma mater, Oberlin College, and awarded a life membership in the Oberlin Friends of the Library at their annual dinner.

Andrew Scrimgeour, Director of the University Library, in August delivered a paper at the International Congress of the International Association for the Empirical Study of Literature--- "Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of the Humanities." He has been elected to the Board of Trustees of Westar Institute and continues as archivist of the Society of Biblical Literature. Recently, he was reelected vice chair of the Executive Committee of VALE, the New Jersey consortium of academic libraries.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, Methodist Librarian, wrote two articles for the spring 2004 issue of Christian History & Biography--- "'I received my commission from Him, brother': How Women Preachers Built Up the Holiness Movement," and "The Lord's Agitators."

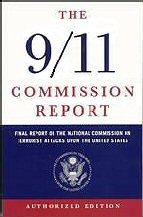

Nearly 200 letters from Drew's extensive collection of Wesley manuscript letters will soon be available on line. The Methodist Library has completed the scanning phase of its Wesley manuscripts digitization project, subsidized by a $5000 grant from the American Theological Library Association's Cooperative Digital Resources Initiative, Phase III.

Drew has completed 590 scans, which represent close to 200 original manuscript letters of John Wesley, Charles Wesley, and other members of the Wesley family. Included as well are hymns and poetical fragments by Charles Wesley, and an unpublished book of poetry by Charles' wife, Sarah Gwynne Wesley, covering the period 1719-1887.

The Wesley correspondence and poetry shed light not only on the history and development of Methodism, but also life in 18th- and early 19th-century Britain. Materials will benefit both scholars and religious researchers with interests in Wesley studies and British history. They will be available on line through ATLA's CDRI database ( http://www.atla.com/digitalresources/ ) in 2005.

In November and December, Drew University Library will exhibit Art for Heart, paintings by children commemorating family members lost during the attacks on the World Trade Center . Administered by the Lower Manhattan Development Project, the exhibit was most recently on view in the School Reception Area at the Museum of Natural History in New York. The project was conceived by teenager Ali Millard, who lost her stepfather on 9/11, and wanted to bring other children together to express their feelings and memories.

Nearly two hundred children participated in art therapy and enrichment programs in New York during which they each created a painting on canvas as a tribute to their loved one. Each image stands as a powerful remembrance rendered through the eyes of a child. The exhibit will be on view in the Main Library and Methodist Library galleries.

VISIONS

NEWSLETTER OF THE DREW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Dr. Andrew D. Scrimgeour, Director

Drew University Library, Madison, NJ 07940

(973) 408-3322 ascrimge@drew.edu

CONTRIBUTORS: Rebecca Barry, Jody Caldwell, Andrew Scrimgeour, Suzanne Selinger, Jennifer Woodruff Tait

PHOTOGRAPHS: Drew University Archives, A. Magnell, D. Strong

THIS ON-LINE EDITION: Jennifer Heise

A complete online archive of past issues of Visions

can be viewed at:https://uknow.drew.edu/confluence/display/Library/Visions+Library+Newsletter+Archive

VISIONS is a semi-annual publication.

© Drew University Library