NetLibrary Brings e-Books to Drew

You have just found the text you want, but it is checked out. You put in a request to borrow the book, and within minutes, you are notified that it is available and you are scanning its pages. Speedy access is just one of the benefits of using volumes from the online resource, netLibrary.

Drew now has permanent electronic access to about 1,200 academic monographs through an agreement with its regional consortium, PALINET, and netLibrary. As with books that can be lovingly held in your hand, e-books can be checked out, renewed, and even reserved for use, but with a check-out period of fifteen minutes, the digitized books are expected to be most useful for browsing, searching, and providing handy reference materials away from the library shelves on a round-the-clock basis. Like other types of online resources, the electronic book format is especially useful for a fast and efficient search through a lengthy text.

The Drew librarians will be interested to learn how use of these titles differs from traditional print monographs.

To find e-books in the Drew catalog, search for an individual title, or browse the collection by searching for "NetLibrary."

From the University Archives:Plantations, Steamboats and Mead Hall: The Gibbons Papers Get Our Attention

By Rebecca Rego Barry

|

Detail from an 1823 letter penned by Cornelius Vanderbilt to his employer, Thomas Gibbons. |

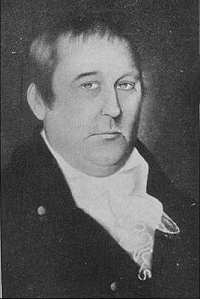

One of the Drew Library's best kept secrets is an archival collection of the Gibbons family papers, located in the University Archives. And just who were the Gibbons? The family holds an important place in American history, although larger names like Vanderbilt often seem to leave the Gibbons in their shadow. Thomas Gibbons, born in Georgia in 1757, had been a lawyer and the mayor of Savannah before moving to New Jersey around 1811. Here he became a steamboat tycoon, whose papers reveal he hired Cornelius Vanderbilt as his captain, and participated in a legal case, Gibbons vs. Ogden, that continues to affect interstate commerce in the United States today.

William Gibbons, Thomas' son, is the man perhaps best known to the Drew community as the builder and owner of Mead Hall, where he lived with his wife and children until his death in 1852. He was heavily involved in managing the family plantations and breeding and racing horses.

|

Thomas Gibbons (1757-1852) lawyer, mayor of Savannah, steamboat tycoon, and one-time employer of Cornelius Vanderbilt., was the father of William Gibbons, who built and lived in the Georgian revival mansion known on campus as Mead Hall. |

The Gibbons papers at Drew span the 1780s through 1840s and include correspondence between the Gibbons men and Cornelius Vanderbilt, Daniel Webster, and a host of other early American business leaders, as well as letters to their plantation overseers in the South. There are legal documents, account books, deeds, books of music, pamphlets and a pardon signed by President Andrew Johnson. It is a collection of national significance, particularly in the areas of economic, legal and cultural history, and over the past year, researchers have begun to re-examine this fascinating set of papers.

Recently increased hours of the University Archives have made possible fuller access and reference service to the Gibbons material and other collections. Additionally, during the fall semester, a long-overdue processing project commenced, which involved organizing and inventorying the collection, placing all documents in acid-free preservation enclosures and writing a finding aid that will be published on the Archives webpage. This effort should ensure that the Gibbons papers not only last another two hundred years, but remain useful research resources to the scholars of today and tomorrow.

The Drew University Archives are open to all members of the University community, as well as other interested people. The Archives are located on G-level of the Library and are open for directed research Mondays and Thursdays 1:00-4:00 p.m. Access to the collection at other times is limited and is by appointment with Rebecca Rego Barry (rbarry@drew.edu, or 973-408-3532). An access policy, as well as indexes and finding aids for the collection, are posted on the Library website, under University Archives.

!class1.jpg |

align=center!First Year Seminar students from Professor Joe Patenaude's class, "The Dramatic Imagination," are guided in their research options by Bruce Lancaster of the Reference Department before scattering for an academic scavenger hunt. |

http://depts.drew.edu/lib/visions/visions14.php#top

In Memoriam: Caroline Coughlin, Former Director

By Lessie Culmer-Nier

The Drew community was saddened by the death of Dr. Caroline M. Coughlin, 58, on September 26, 2003. Serving as a Drew librarian from 1978, she was Director of the Library from 1986 to 1994.

During her tenure at Drew, Caroline presided over the recently completed Learning Center and took the Library into the digital age by selecting the first automation system. She nurtured the new Friends of the Library begun under her directorship and established the Endow-a-Book Fund.

Caroline helped mold the Drew librarians into a faculty and advocated equitable compensation for all staff. She encouraged individuals to do their best and to stretch themselves. She supported librarians in pursuit of advanced academic degrees, staff in pursuit of library degrees, and any library employee who wished to take on new areas of knowledge and responsibility, always trying to match person to person, person to job, and person to opportunity. She built a library staff and faculty known for its excellence, collegiality, and service orientation.

Caroline was active in the American Library Association. Her publications centered on library administration and information resources management. Twice she revised the standard text, Lyle's Administration of the College Library.

She received the Distinguished Service Award from the New Jersey Library Association's College and University Section and was a Senior Fellow in the UCLA Senior Fellows Program.

After leaving Drew, she returned to teaching as a visiting scholar at Rutgers, and elsewhere, including library schools in Wales and Finland. Multiple sclerosis, and more recently, other illness, sapped some of her energy, but not her optimism.

Here she is remembered in verse written, and recited in her presence, by the late Professor of English Emeritus, Robert L Chapman.For Caroline

Let us utter a hearty hale and sad farewll

To her who brought the OAK and ROM and menu,

And other cyber-sorcery as well

To our previously printish venue,

For this salutary great leap forward

We thank our Caroline with all our hearts.

As we lead her lachrymosely doorward

We laud her wit, tenacity, and smarts...

[Excerpt from a poem composed and given on May 17, 1994, on the occasion of the departure of Caroline Coughlin from Drew.]

Recent Gifts to the University Library

Mrs. Hilja Wescott has donated to the University portions of the library of her late husband, Professor Roger Wescott. The volumes range among the fields of anthropology, linguistics, history, and sociology.

The Friends of the Library received a generous gift from Cynthia Cavanaugh, Ph.D., Caspersen School '03, to be used for restoration of older books in the literature collections. Her acknowledgement of the Library's Interlibrary Loan staff in providing books for research over the past four years was also much appreciated.

Mr. Finn M. W. and Dr. Barbara Morris Caspersen have donated a collection of limited editions of classic works, many of which are in fine bindings, as well as a set of audiotapes comprising the publisher's selection of the one hundred greatest books ever written.

The Library gratefully acknowledges the generosity of Miss Julia LaFalce for her continued support.

Last spring, the Drew College Democrats earmarked funds to purchase several library books with progressive and liberal themes. Twelve books were selected in consultation with the political science faculty and the head of collection development. Among the titles are What Liberal Media? by Eric Alterman, We're Right, They're Wrong by James Carville, and Jennifer Delton's Making Minnesota Liberal: Civil Rights and the Transformation of the Democratic Party.

The Library acknowledges with thanks the donation of Professor Patrick O. Dolan.

Dr. David Altschuler has contributed a large number of books from his library in Jewish history, Holocaust studies, theology, ethics, and biblical studies.

A collection of books on historic preservation and historic architecture in the United States has been added to the Library holdings through the generosity of Karen Morey Kennedy. The gift of over three hundred books from her professional library supports the University's certificate program in historic preservation, as well as history and art courses in the College.

Brian Bucci has made a much appreciated contribution to the Book Endowment Fund.

|

Well Versed in Science...Reference Librarian Sarah Oelker instructed First Year Students from Professor Jim Supplee's seminar, "Special Relativeity," this fall. |

Books on Walls, Books on Ceilings

By Andrew D. Scrimgeour, Ph.D., Director, University Library

Fall Commencement Address

Drew University, Madison, New Jersey

October 25, 2002

I

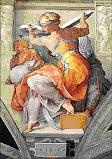

Last year I visited the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, the holy of holies of Renaissance art. I stood transfixed under Michelangelo's iconic story panels that flesh out the early chapters of Genesis. The famous ceiling-where God is transfusing life into Adam's outstretched arm and is so exhausted by it that he must be supported by angel midwives-that same ceiling is awash with iridescent color, recently cleansed from centuries of color-corrosive candle-smoke.

After a while I noticed twelve large figures on its fringe-women and menalternating around the vast rectangular ceiling. The women were Greek and Roman seers; the men Hebrew prophets-Isaiah, Cumaea, Daniel, Libyca, Jeremiah, Persica, Ezekiel, Erythraca, Joel, Delphica, Jonah, and Zechariah. What caught my eye is that most of them carry a book or are within reach of one. Some are studying books; others have them nearby, not as props but as tomes that they have just consulted. Books circle the ceiling.

Then I began to see the space in a new light. The canopy of the Sistine Chapel is not only a majestic roof; it is a lofty, inverted reading room. It is where Michelangelo, lying on his back on a scaffold, spread his pages with trowel and pigment and fashioned fresh interpretations of the nearby canonical texts. The frescoes of the Creation, Fall, and Flood are not isolated panels but dramatic drafts flowing from the reference collection circling the ceiling.

The book theme does not stop with the ceiling. The west wall, above the altar, portrays the end of human history in the haunting Last Judgment scene. On that wall books not only capture the past, they determine the future. Christ stands high and central, the judge of all humankind, directing traffic into eternity. His decisions are dictated by non-negotiable entries in a two-volume set held by angels, the Book of Life and the Book of Death.

Books, for Michelangelo, anchor the imagination and fuel the prophetic spirit. Books are not peripheral to life, they are central. So they inhabit the loftiest spaces. That was spirit of the Renaissance, and it still animates the humanities today.

Earlier this month many of us gathered under the vault of Drew University's grandest space, the Great Hall in its Collegiate Gothic splendor, to celebrate the arrival of the Willa Cather Collection--the distinctive collection amassed by the late Frederick Adams of the Morgan Library. Why is it that when we want to celebrate books we often choose exalted chambers?

Why is it that some library buildings resemble cathedrals or have reading rooms with stained glass windows? My boyhood love affair with books flowered in the august public libraries of Salem, Oregon and Boise, Idaho--libraries that bore the name "Carnegie." Andrew Carnegie, the philanthropic Scot, not only financed some 1,700 public libraries throughout the United States, he dictated their design. Only stately, classical architecture made an appropriate public statement of the value of the library for a community. Our own Rose Library, with its Greek Revival Ionic colonnade is an inspiring structure, as was the original library. The Cornell Library no longer stands, but the English stained glass window that was its crowning glory graces the entry of our newest library building.

Why is it that we take great pains to shelve our personal libraries in the best possible way? Some of us chronicle our careers by the evolution of our bookcases, those walls within walls. First came the affordable, modular bookcases--the ever-expandable bricks and boards that served us during college and graduate school. Do you remember?

They were also highly portable. I recall pushing this feature to the limits one Saturday morning while helping a friend move. We discovered that the easiest way to move bricks from a third-floor apartment was to toss them out the window to collaborators waiting on the ground below! Bricks and boards were supplanted by unfinished pine bookcases with their flimsy backs of particle board. We sanded, stained and shellacked those cases with great care. It seemed we had finally arrived when we could purchase real furniture--finished mahogany and cherry cabinets, or even an antique piece or two. I hope a bookcase or two are among the surprises that await some of you later this evening.

We hold book celebrations in exquisite rooms, house books in temple-like edifices, and place our personal volumes on the best possible shelves. Why? Because, as they were for Michelangelo, books are central to our lives, and we must honor them.

That this is true in the humanities is existentially clear to many of you graduates and your families. Those of you in the Ph.D. and D.Litt. programs wrote lengthy manuscripts en route to your doctorates. It was a requirement of the program and the international standard. It was not an essay, not a book review, not an article, nor an interview, but a book. In the process of writing your dissertations and theses, you conducted interviews, analyzed images, visited web sites, and read manuscripts, journal articles, newspapers, and essays. Yet most of your time was spent studying books. Recently, I had a small study done on dissertations that have been completed at Drew in the last two years. An analysis of their bibliographies showed that the average number of items in the bibliographies was 185. Of that number, seventy four percent were books; twenty five percent were journal articles. Books predominated overwhelmingly, three-to-one.

If you want to see this fact dramatically illustrated, just walk through the Pilling and Baldwin rooms, the graduate study rooms in the library. Without exception, each study carrel is a serious repository of books. In many of them, books are stacked in ungainly, teetering piles, resembling poker chips in a high-stakes game. This is because the monograph is the bedrock of scholarly communication in the humanities. Unlike science and much of the social sciences where the journal article is the coin of the realm, philosophy, religious studies, history, literature, and the arts trade in extended treatises.

II

Some of you must be wondering, "But is not technology radically changing this picture? Are not books on the way out?" There are absolutely no empirical indicators to warrant that claim. There are experiments with electronic texts, with oxymoronic names like "e-books," but they have not caught on. Certainly there is plenty of hype from the technological gurus, including Bill Gates. Last year in a press conference in Madrid, he avowed that he expected to accomplish his highest goal before he died. That goal, he explained, is to put an end to paper and then to books. 1

Technology has dramatically changed the way we do business in the library, even though it hasn't created an heir to the monograph:The noble card catalogs are gone and have found fashionable second careers as ideal wine-storage cabinets.

The online catalog is accessible from dorms , indeed from anywhere in the world, and can tell you if a volume is checked out or not and can link you with a keystroke to hundreds of journals, for increasingly we purchase them as electronic subscriptions.

Reference works that need to be updated regularly, like encyclopedias and indexes to journals, are thriving in electronic form.

The tedium of research has been eased by computer technology.Increasingly, we will put portions of our special collections into electronic form so that they can be used internationally. Right now, the web page for our internationally renowned Methodist collections averages 11,000 hits a month.

And the flow of paper from the library computers gushes like a geyser, for our students love the computer for locating resources, but they want to read the material in hard copy. On the Sistine Chapel ceiling, God reaches out to create; in the Drew library, students reach out to click the print button.

Meanwhile, the book remains in its traditional form.

Curiously, technology is becoming less and less a differential in evaluating top-tier, liberal arts-focused, college and university libraries. Nationally ranked schools, in Drew's peer group, all have about the same range of electronic services and resources. Ironically, the badge of distinction among these schools is returning to a classic marker--the size, range, depth, and currency of the book collections.

This news is troubling in some quarters. Over the past twenty years, many colleges and universities sacrificed their book budgets in order to pay for the new technologies and the spiraling costs of journals, believing the hype that the book was to be eclipsed by digital surrogates "any day now." Other institutions inadvertently created a linguistic Lourdes where their libraries, crippled from years of mediocre funding, suddenly were to be healed by a dip in the waters of technological hyperbole.

Meanwhile, the publication of academic texts grew rather than declined. Ask any respectable professor in the humanities to restrict his or her lectures, discussions, and assignments to digital sources and you will be ridiculed for betraying your ignorance of the sources that comprise the scholarship of the field.

III

But why do books continue to thrive? Why do they remain central to our lives? Practical answers ripple off the tongue:

- They are so portable. You can take them anywhere--home, office, car, train, plane, beach, and bed.

- You can work with quite a number of them simultaneously if they are within easy reach.

- They don't require a technological intermediary; they don't come with batteries.

- Black print on white paper is easy on the eye and ideal for extended periods of reading.

- Memorization is enhanced when the text is fixed and you can see the passage on a particular place on the page.

- You can mark them up.

- You can mark your place.

- You can store things in them.

- You can hide things in them.

- You can impress people with them.

- They are ideal gifts for any occasion for just about anybody and in any price range.

- You just can't bear to throw one away.

To this practical inventory must be added a critical observation: essential discourse in the humanities requires extended argumentation and narrative. Some texts are unabashedly linear and are meant be read from beginning to end. Some texts cannot-dare not-be reduced to information. The codex is the ideal package for scholarship and literature. Here form meets function, a marriage made in heaven.

So we line our walls with them, spend the milk money on them, read them aloud, converse with them, argue with them, learn from them, raid them, edit them, translate them, write more of them--and plead with the university for larger offices with wall-to-ceiling bookcases to house them, lest our spouses require us to sleep in them as well.

Books also possess sensuality. They are meant to be touched. They are meant to be held--on the lap or desk, tilted upward, and grasped between the thumb and forefinger. They are meant to be caressed, page by page with a gentle downward motion, sometimes with just a hint of moisture from the forefinger.

Bill Holm, the Minnesota prairie author, makes this confession:I love the bite of lead type on heavy rag paper, the sexy swirls of marbled end papers, the gleam and velvety smoothness of Morocco calf, the delicate India paper covering the heavy etching of the frontispiece, the faint perfume of mildew in old English editions, the ghost of smells of ink and glue in bindings.

The first time I visited a Russian Orthodox church, I watched the black-mustached [bishop] emerge from behind his gold door in a great cloud of incense. The choir surged louder in four almost-in-tune parts.

[He] bent ceremoniously down and kissed the Book. That's right, I thought! The right thing to do with a book! I will go home to Minnesota and light a candle and every night I will kiss a book. Tomorrow Leaves of Grass, and after that The Iliad and after that The Well-Tempered Clavier....2

Which books would you kiss?

If we are wise, we let poets have the last word. So let us be wise. Here is Billy Collins, a recent Poet Laureate of the United States:From the heart of this dark, evacuated campus

I can hear the library humming in the night,

a choir of authors murmuring inside their books

along the unlit, alphabetical shelves,

Giovanni Pontano next to Pope, Dumas next to his son,

each one stitched into his own private coat,

together forming a low, gigantic chord of language.

I picture a figure in the act of reading,

shoes on a desk, head tilted into the wind of the book,

a man in two worlds, holding the rope of his tie

as the suicide of lovers saturates a page,

or lighting a cigarette in the middle of a theorem.

He moves from paragraph to paragraph

as if touring a house of endless, paneled rooms.

I hear the voice of my mother reading to me

from a chair facing the bed, books about horses and dogs,

and inside her voice lie other distant sounds,

the horrors of a stable ablaze in the night,

a bark that is moving toward the brink of speech.

I watch myself building bookshelves in college,

walls within walls, as rain soaks New England,

or standing in a bookstore in a trench coat.

I see all of us reading ourselves away from ourselves,

straining in circles of light to find more light

until the line of words becomes a trail of crumbs

that we follow across a page of fresh snow;

When evening is shadowing the forest

and small birds flutter down to consume the crumbs

we have to listen hard to hear the voices

of the boy and his sister receding into the woods. 3

So graduates, as you leave this forest 4:Follow the trail of crumbs across pages of fresh snow.

Now a final toast:May the shelves on your wall be full.

May the book stacks on your desk

and by your bed be high.

And may books circle your ceiling, too.

Godspeed

1 Mario Vargas Llosa, "Why Literature?" New Republic (May 14, 2001), 33-34.

2 "Confession of a Bibliophile," Utne Reader (April 2001), 82.

3 Collins, Billy. "Books," Sailing Alone Around the Room: New and Selected Poems (Random House, 2001), 12-13.

4 Drew University is affectionately known as "The Forest.>"

Professional News

Rebecca Rego Barry, Archives Assistant (MA, Caspersen School, '01) has been awarded the Book History Graduate Student Essay Prize for 2003, for her article, "The Neo-Classics: (Re)Publishing the 'Great Books' in the United States in the 1990s." The essay appears in the 2003 issue of Book History.

Jody Caldwell, Head of Reference, spent last year's half-time sabbatical completing a year of course work in the Caspersen School Ph.D. program in Religion and Society.

Linda Connors, Head of Acquisitions and Collection Development, presented "Moral Values in Post-Napoleonic Periodicals: The British Experience" at the eleventh annual meeting of the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading and Publishing, in Claremont, California, in July.

Cheryl King, Cataloging Associate, has published her first book, Michael Manley and Democratic Socialism: Political Leadership and Ideology in Jamaica (Eugene Oregon: Resource Publications. Imprint of Wipf & Stock, 2003). It focuses on the Democratic Socialist leadership of Michael Manley, Prime Minister of Jamaica from 1972 to 1980, and the impact of his ideology on Jamaican politics. King holds an MA in Political Science from the City University of New York, as well as degrees from Hunter College and the University of the West Indies.

Andrew Scrimgeour, Director of the University Library, gave the Fall 2002 Commencement Address at Drew, speaking about "Books on Walls, Books on Ceilings." The essay appears on the preceding pages of this newsletter. He also served as Vice Chair of the Executive Committee of VALE, the New Jersey consortium of academic libraries, and continued as Archivist of the Society of Biblical Literature.

Suzanne Selinger, Theological Librarian, collaborated on the translation into German of her book, Charlotte von Kirschbaum and Karl Barth (Penn State, 1998).

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, Methodist Librarian, delivered several papers at conferences, including "The Real Presence at the Lord's Table in the Wesleyan Tradition" at the conference on War and Peace in the Wesleyan Tradition in Ocean Grove, N.J., in July. A related paper was published in the July 2003 issue of Methodist History as "John Calvin, the Wesleys, and John Williamson Nevin on the Lord's Supper." In October, she presented "The Sacred True Effectual Sign: John Calvin, the Wesleys, John Williamson Nevin, and a Protestant Real Presence" at the Wesley 300th celebration at Asbury Theological Seminary.

Elise Zappas, Humanities Cataloger and Automation Librarian, was on sabbatical leave last spring, to complete her Drew Master's thesis in English Literature.

Library Exhibits

|

The 2003 tercentenary of the birth of John Wesley, founder of Methodism, was marked this fall by a traveling exhibit, "Wesley in America," hosted by the Methodist Library and the General Commission on Archives and History. |

Main Library

November 3, 2003--January 31, 2004

Lyrical Watercolor - Guache and acrylic paintings by Joan Pittis, College alumna from the class of 1974 and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art at Drew. Sponsored by the Drew University Alumni/ae Association.

The Many Faces of the Wesleys from the Collections of the Drew University Library will remain on display through November.

December 1, 2003-January 31, 2004

New Book Acquisitions

February 2-March 1, 2004

Selections from the Jacob Landau Archive. This exhibit documents the career of the New Jersey artist whose work will be concurrently on display in a major exhibition at the Dorothy Young Center for the Arts on the Drew University campus.

|

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, Methodist Librarian, will curate an exhibit on woman preachers of the 19th century from the Methodist tradition, to go on view in the Methodist Archives Center in February. |

Methodist Archives Center

November 7, 2003 - February 1, 2004

Methodist History Exhibit from the collections of the United Methodist Archives Center

February 2 through March, 2004.

Women Holiness Preachers

About Visions

VISIONS

NEWSLETTER OF THE DREW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Dr. Andrew D. Scrimgeour, Director

Drew University Library, Madison, NJ 07940

(973) 408-3322 ascrimge@drew.edu

EDITOR: Anna S. Magnell

PHOTOGRAPHS: Drew University Special Collections, A. Magnell

THIS ON-LINE EDITION: Jennifer Heise

A complete online archive of past issues of Visions

can be viewed at:https://uknow.drew.edu/confluence/display/Library/Visions+Library+Newsletter+Archive

VISIONS is a semi-annual publication.

© Drew University Library