Randolph Sinks Foster (1820-1903) was the second president (1870-1873) of Drew Theological Seminary, later Drew University.

Dr. Foster was the third of that first flight of Drew teachers - McClintock and Nadal were the others - whose connection with the school was brief but notable. He came out of a very different background - was in fact a Westerner, born in an Ohio county jail, of which his father was the keeper. His grandfather, adventuring into Kentucky from Virginia, had been killed by the Indians in that "dark and bloody ground."

Young Foster gleaned such schooling as he could in Ohio and entered Augusta College, in Kentucky, the earliest Methodist college west of the mountains, where a little faculty, headed by the versatile Martin Ruter, and numbering such future leaders as John P. Durbin and Henry B. Bascom, was trying to light a torch for the sons of the pioneers.

Tall and lithe, with a piercing eye, and a vein of poetry in his soul, this youth of 17 found more satisfaction in preaching up and down the countryside than in listening to lectures on theology or Greek literature and mathematics. Unwise friends advised him that he was called to preach, and should set about it without delay. So he dropped his books and went to the session of Ohio Conference in 1837 seeking admission on trial. His sponsor recommended him as "A splendid young man." This brought the old stager, David Young, to his feet. "Mr. Bishop," he said, "You are new to the West and do not know our ways. Out here we call a potato splendid!"

But Randolph Sinks Foster was no small potato. He began riding circuits in the Ohio Valley as a junior preacher, and soon realized that he had made a mistake in leaving college. But he had the sense to perceive that by intense application to the means of self-culture that came within his reach he might in some degree make up his deficiencies.

Before he was thirty he had an opportunity to exhibit the unusual quality of his mind. The struggle between Calvinism and Arminianism was at its height in that section, and a Presbyterian minister brought out a book which dealt with the doctrine of Election and Free Grace in a challenging way. It was not easy to answer, but it had to be answered. Young Foster took it upon himself to make the reply, in the form of a series of letters to the Western Christian Advocate, of which Matthew Simpson was editor.

The pebble from his sling smote Goliath between the eyes. He was hailed far and wide as the champion of the Wesleyan faith. His stature loomed so high that he had invitations from Atlantic seaboard churches, and was soon preaching to the principal congregations of New York, and associating on equal terms with the leaders of Methodism.

Northwestern University at Evanston, Ill., was just struggling to its feet, and, needing a strong man for president, turned to Dr. Foster. He remained there only three years - long enough to win the affection and esteem of the student body and the admiration of the public, and quite long enough to convince himself, and probably others, that educational administration was to his forte. He reisgned and returned to the pastorate and the pulpit where he reigned.

He had been Mr. Daniel Drew's pastor in Mulberry Street and enjoyed many opportunities of discussing the ways in which wealth might be applied to the service of the church. He was one - though by no means the only one - who claimed to have brought the founder's mind to its decision to build and endow a theological seminary near New York. Perhaps he might have been its president, - he thought so! - but, with the Evanston experience still fresh in his mind, he waived the offer in favor of McClintock.

However this may be, he was named as first occupant of the chair of Systematic Theology, which he held from 1869 until his election as bishop in 1872. Meanwhile death had vacated the presidential office, and because of his close relations with Daniel Drew and his supposed influence with him, Professor Foster was considered the most available man for president, and was accordingly elected.

It is evident that these conditions were unfavorable to a man who was addressing himself for the first time to the teaching profession, and we do not find much evidence that he impressed himself greatly as an instructor upon the few classes over which he presided. Had conditions been otherwise, he would have probably been a marked success. For Systematic Theology was a world in whch he was at home. He had studied it with delight for years. He had made himself familiar with its literature, and, when release from episcopal duties left him free to follow his bent, he devoted the rest of his life to the writing of his Studies in Theology, though he lived to complete only six of the projected eleven volumes. This undertaking was to have been his magnum opus.

But he had unfortunately delayed too long. While occupied with many official duties here and there around the world, he had vailed to keep in touch with the theological thought and literature of a new generation. He had worked diligently and meditated deeply. But most of what he now had to say no longer had an appeal to the public to which it was offered.

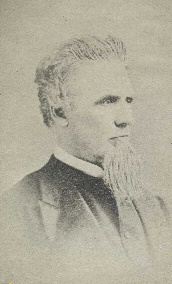

Yet he should not be judged by this ill-advised adventure. His fame will abide as that of one of the most powerful and compelling preachers who ever graced the Methodist pulpit. To look upon him at such times was an inspiration. For in face and form he presented a magnificent appearance. He was tall, erect, strong of physique, with piercing eyes, and abundant hair and beard, which in his later years were snow-white. Never light or trifling in speech or manner, he always maintained a becoming dignity without stiffness.

Reproduced from The Teachers of Drew, 1867-942, A Commemorative Volume issued on the occasion of the 75th Anniversary of the Founding of Drew Theological Seminary, October 15, 1942. Edited by James Richard Joy. (Drew University, Madison, N.J., 1942)

Courtesy of the Drew University Archives